- Home

- Gail Carson Levine

The Two Princesses of Bamarre Page 2

The Two Princesses of Bamarre Read online

Page 2

Trina put both hands over her face. “Don’t let it hurt me!”

Using his baton, Rhys gathered the cloud and shaped it into a pillow.

I began to smile. Trina peeked between her fingers. Milton stood up to see better.

“Sleep is always sweet when your pillow is a cloud.” Rhys stepped to her bedside. “Lean forward.”

“You’re sure it’s safe?”

“Perfectly safe.”

She did as she was directed, and Rhys placed the cloud pillow behind her. I could see that his touch was gentle.

“There,” he said. “Now lean back.”

“I’ll go right through it!” She lowered her back gingerly while scowling at Rhys. The scowl vanished. “It is a trifle better.”

“Why, look at that!” Milton said.

I laughed, and spoke before I could think. “The pillow won’t rain, will it?”

Rhys laughed too, harder than I had. “Rain! I never thought of that. Pillow rain.” He shook his head, still chuckling. “It won’t rain, and Trina’s dreams will be lovely.”

She sighed deeply and closed her eyes. “I think I’ll take a nap now.”

I didn’t want her to nap. I wanted her to listen to me. I appealed to Milton. “Trina should struggle against the Gray Death, shouldn’t she?”

“It can’t hurt her to try, but she should sleep now. She won’t get much rest tomorrow.”

I must have looked puzzled, because he added, “One of your father’s carriages will take her home to her family tomorrow.” He tucked the blanket in around her. “Trina, you’ll think over Her Highness’s suggestions in the carriage, won’t you?”

She nodded with her eyes still closed. I supposed that was something. But I wished I could slip into her cloud-sweetened dreams and persuade her there.

Chapter Three

* * *

RHYS WALKED down the corridor with me. “Your Highness, I see your beautiful embroidery everywhere I look in the castle. I’m so happy to meet the artist.”

“Thank you,” I murmured. “They’re not very good.”

“But they’re very good.”

I felt myself blush. I didn’t say anything, and we were silent for a few moments.

Then he said, “Making cloud pillows is one of the first lessons a sorcerer learns.”

I wondered what the others were, but I was too shy to ask. He was a beginner, as all our sorcerers were. They could fly, of course. All sorcerers could. Their training included five years in the service of a king, for whom they performed minor magic, did simple tricks with the weather, and kept the castle free of rats.

If he could keep rats away . . .

“I’m sorry about your chambermaid.” Rhys sighed, an elaborate exhale. “I suppose it’s silly to feel sad over someone I hardly know, but you see, sorcerers don’t get sick. We’re never ill, so illness seems tragic to me.” He waited for me to say something.

“Er . . . that’s interesting.”

We reached the winding stone stairs that descended to the lower floors of the castle. The stairs were too narrow for us to go down side by side, so Rhys chivalrously went first. He looked over his shoulder to continue the conversation. “It is interesting. It’s interesting how different we are from other creatures—how different we are from humans, and how different humans are from elves and elves are from dwarfs and dwarfs from sorcerers. It’s fascinating.” He smiled, then frowned. “Are you afraid of becoming a victim of the Gray Death?”

I shook my head.

“You’re brave, Princess Addie.”

No one had ever called me brave before. It made me feel strange, as if I were impersonating someone, as if Rhys had mixed me up with Meryl.

“Do you think . . .” I hesitated, then said in a rush, “Could you rid the castle of spiders?” He wouldn’t think me brave now.

He stopped, and I almost crashed into him. “I think I can.” He paused, then nodded vigorously. “Certainly I can.” He turned all the way around. “I’ll do it tonight. Ugly little beasts, aren’t they?”

He didn’t like them either!

He started down the stairs again. I smiled at his back. “Thank you.”

He stopped and turned again. “You’re welcome.” He bowed, managing to be dramatic, even in the cramped stairwell.

I had to curtsy too, and then we set off again.

After a few steps he said over his shoulder, “In sorcerers’ years I’m a bit older than you are, but not a great deal older. I’m seventy-eight. If I were human, I’d be just about seventeen.”

Seventeen at seventy-eight! How long did they live?

“I envy human children. You learn everything you need to know so quickly. We can speak and even fly when we’re born, but beyond that we learn almost too slowly to bear.”

We reached the bottom of the stairs.

He bowed yet again. “I must leave you now. I look forward to speaking with you again.”

He did? So did I!

Back in the nursery Bella was alone, crocheting. I picked up my embroidery, but I was too distracted to work on it. My thoughts kept revolving from Trina to Rhys to no more spiders and back to Trina again.

In half an hour Meryl came in from her swordplay and stood at my shoulder, looking down at my work. She laughed. “I like that! What made you think of it?”

Usually I embroidered scenes from Drualt, but this embroidery showed a close view of one of the dozens of gargoyles that adorned Bamarre castle. The rest of the castle was visible in the background—the coral-colored stone walls, the blue tower roofs, the slitted upper windows, and the vaulting arches between tower and buttress.

The gargoyle in the foreground was a gryphon’s head, with fierce bulging eyes and a bone in its cruel beak. Next to it a real gryphon hovered in the air, its beak hanging open in astonishment. The real monster appeared much less dangerous than its twin in stone.

“I don’t know why I thought of it,” I said. But I did know. I had invented the scene to comfort myself, to tame one monster at least.

I changed the subject. “Has anyone ever caught the Gray Death and lived?”

Bella answered, “Your father hears about cures now and then, but it always turns out that the person didn’t have the Gray Death in the first place.”

“Do you think the fairies could cure Trina?” I said.

“I have no idea.”

“Bella!” Meryl said. “Certainly the fairies can cure the Gray Death. They can do anything.” She picked up her thick book about battles with monsters and sat in our gilded throne chair.

Fairies hadn’t been seen by humans for hundreds of years. They were believed to have retreated to their home atop the invisible Mount Ziriat. They still visited the elves and sorcerers and dwarfs occasionally, but never humans.

They were sorely missed. We used to have fairy godfathers and godmothers. Fairies had known our best selves better than anyone else, and they’d encouraged us and given us a boost when we were in trouble. There were fairies in Drualt, and the hero himself was believed to have visited them on Mount Ziriat. But that might have been fable. We had no certainty about any of Drualt’s life—or even whether he’d lived or not. He might have been merely the invention of a long-ago anonymous bard.

Meryl said, “Someday I’ll find the fairies and persuade them to come back to us. If I haven’t found the cure by then, I’ll get it from them.” She turned a page in her book. “Addie . . . do you want me to search for them now so they can save Trina?”

My heart skipped a beat. No! No, I didn’t want her to search. I didn’t want her to go anywhere.

Bella exploded. “Search for fairies! You’re a princess. Not a knight, not a soldier, a princess!”

“Do you want me to, Addie?”

“No,” I said quickly. “I think Trina will rescue herself. She promised to consider my method.” Under my breath I added, “Besides, you can’t go. I’m not wed yet. We have a bargain.”

Chapter Four

&nbs

p; * * *

AFTER DINNER THAT NIGHT I returned to Trina’s chamber, but she was asleep, and Milton wouldn’t let me wake her. Then, before I awoke the next morning, a carriage took her away from Bamarre castle.

I thought of her often in the weeks that followed. I decided that she must be defying the Gray Death. She might hesitate at first, but as she weakened, she would become frightened and then she’d begin to struggle. I imagined her forcing herself to stand and then to walk, then to go outdoors. I imagined her reveling in her restored health.

I thought of Rhys often too. He kept his promise, and I saw no more spiders. I was grateful every time I stepped briskly into a room or walked confidently down a corridor. I told Meryl about the spiders’ banishment, and she rejoiced with me, but she had little interest in Rhys since he didn’t ride a horse or wield a sword.

I wondered how he had accomplished the spider miracle and the cloud trick. I knew little about sorcerers, although I knew about the spectacle of their birth. They were born when lightning struck marble, which happens rarely enough. They had no parents and no brothers or sisters.

People wealthy enough to own marble put a slab of it outdoors during storms in hopes of witnessing a birth. Father always did so, but we’d never been lucky.

When a birth occurred, the lightning and the marble begot a flame that grew and unfolded as might a quick-blooming rose. Within the flame would be the sorcerer—full grown, still glowing, his nakedness covered by a shimmering cocoon.

He would look about him for a moment. Then he would look inward and learn what he was. In a burst of joy he would rocket into the sky, into the storm, showering sparks. The speed of his flight would burn off his cocoon, but a spark of the flame that gave him life would burn on in his chest, sustaining him until death.

This was all I knew. To learn more, I went to the library and looked sorcerers up in The Book of Beings. After the description of their birth, I read:

Life span: Sorcerers need only air to live. They may eat and drink for pleasure, but they need not. They are incapable of sleep. Although they never take ill, they may die in as many other ways as humans can, by accident or by design or in war. If they do not meet with disaster, however, then at the end of five hundred years their spark is extinguished, and they die.

During their first two hundred years they are apprentices, and they live out in the world. At the end of that time, they are journeymen and retreat to their citadel, which they rarely leave again.

Appearance: Their most distinguishing feature is their white eyelashes. All sorcerers, whether male or female, young or old, have dark wavy hair. The species runs to tallness: The average height of a female is five feet and ten inches; the average height of a male is six feet and two inches. All have long, tapering fingers and long, graceful necks. The faces are individual, with as much variety of feature as is seen in humankind. Immature sorcerers have the open, unlined faces of youth.

Disposition and relations with humans: Sorcerers are neither universally good nor universally bad. There have been heroes and villains, but most sorcerers, like most humans, are a blend of good and bad qualities.

Although most are indifferent to humans, some of the young go through a phase of intense interest that always terminates at the end of their apprenticeship. Sorcerers rarely marry, and they never marry each other. A few marriages between sorcerers and humans have occurred, and children have been born of such unions.

The section ended, and I slammed the book shut. It hadn’t told me what magic the sorcerers could do, what went on at their citadel, or even how many sorcerers there were.

Rhys and I did speak again, but not often. Father kept sending him off to distant regions, to help farmers with the weather and to report on monster depredations.

I met Rhys a few times by accident in the castle corridors. Each time, he stopped to talk. Once he told me of a fair in Dettford where a performer had danced a jig on the heads of ten villagers, who could hardly stand still for laughing. Another time he described a tapestry in an earl’s castle that illustrated the meeting between Willard, an early Bamarrian king, and the specter that had predicted the cure to the Gray Death. He added that the tapestry was almost as skillfully done as my embroideries.

But he never sought me out. I saw him most often during dinner in the banquet hall. Indeed, in his peacock’s attire, he was hard to miss.

He was very different from me. He was dramatic. He smiled easily, frowned easily, and laughed easily and with abandon, head thrown back, shoulders heaving.

Once I saw him fly. I had been sitting in my window seat, sketching. It was a gray day, and a fine mist was falling.

He stood with Father in the courtyard. Father read something from The Book of Homely Truths, the book of sayings he quoted constantly. Then he closed the book and raised his hand in a gesture of parting. Rhys lifted effortlessly, as smoke rises. From a few feet up he bowed to Father. Then he sailed off—backward. I was beginning to know him, and I suspected that he was showing off. I wondered if he knew I was watching.

Before I met Rhys, I’d been infatuated with Drualt for years. I used to put myself to sleep at night by imagining meetings with him. I’d tell him my long catalogue of fears, and he’d comfort me and describe his adventures.

But now I imagined meetings with Rhys instead. I wouldn’t mention my fears, because I wanted him to think well of me. In their place I told him about my sketches and my embroidery designs, and he told me about his experiences in Bamarre. At some point he always mentioned that he adored talking to me, and I always blushed and mumbled that I liked talking to him too.

I’d never before been infatuated with someone living, someone real. However, infatuation with Rhys was as foolish as infatuation with a legendary hero. I was still a child, and Rhys was a sorcerer.

When I was sixteen, Father began building a new wing to Bamarre castle. Rhys was needed to straighten walls and to keep stones from falling on the laborers.

The sitting room that had been our nursery overlooked the work. Whenever I had time, I’d sit there with my embroidery and watch. Once Rhys saw me and waved.

Then, after a week, he took pains to find me—and Meryl and Bella too. He stationed himself in the garden, along the route we took on our afternoon walk.

The irises were in bloom, and I had been thinking of sketching them when we turned into the rose walk. There was Rhys, seated on a bench, head tilted back, breathing in the perfumed air so deeply that I could see his chest rise and fall.

He sprang up, and I felt Bella stiffen. She considered sorcerers to be outsiders, and she distrusted them.

When we got near, he bowed. “Princesses, Mistress Bella.” That day his doublet had green-and-blue stripes, and his boots sported golden spurs.

The three of us curtsied.

“I have gifts for you, if I may.” He picked something up from the bench, a sword in a silver scabbard. He knelt to present it to Meryl. “I believe you like to fence, Your Highness.”

She took the sword and drew it out of the scabbard. “It’s beautiful.” She held it out for me to see. “Isn’t it splendid?”

It was, but I hated it. She had no need for a sword, not while I was still unwed.

She must have seen something in my expression, because she touched my shoulder and said in a low voice, “Stop worrying, Addie.” Then she began to fence with a rosebush. “Take that, you dastardly roses. Take that.” She parried and thrust, handling the sword easily, as graceful as a festival dancer.

“Meryl, a princess doesn’t—” Bella began.

“See how it catches the sunlight? Sword, I dub you Blood-biter.” Blood-biter was Drualt’s sword. “I’ve longed for a sword, but . . .” She looked up at Rhys. “How did you know?”

He smiled. “You’ve been seen practicing with a wooden training sword.”

“Thank you. I’ll use it well.”

Don’t use it at all!

“I have something for you too, Mistress Bella.” Rhys reac

hed into the pouch at his waist.

“I can’t accept a . . .”

Her voice tapered off as Rhys drew out an object I’d never seen before. Meryl stopped fencing and came close to see.

It was the size of my hand, pearly white with tints of rose and blue, wide at one end, coming to a point at the other.

“Is it?” Bella breathed.

“Yes. It’s a scale from a dragon’s tail.”

Bella reached for it.

“Take care. The tip is very sharp.”

“Did you slay the dragon?” Meryl asked in a hushed, reverent tone.

Bella took the scale by the wide end. “Thank you, Rhys.” She curtsied.

He bowed yet again. “No, I didn’t slay the dragon. The scale comes from our sorcerers’ citadel, where there are many wondrous things.”

I hoped he had something for me too. “Can I touch it?” I asked.

Bella held it out. It felt warm, and so dry it seemed to draw moisture from my finger.

“Does it have any power?” Meryl said.

Bella opened her mouth to answer, but Rhys spoke first. “It’s versatile, Princess Meryl. Hold it in your hand, and you’ll be cozy warm on the coldest day. Place it on your mantel, and mice and rats will stay away from your hearth. Boil it in a pot, and you’ll have a tasty broth, fiery and a little bitter. Take it out of the pot, dry it off, and it makes a superior letter opener.” He bowed yet again.

Bella placed the scale carefully in her reticule.

“And the best part,” Meryl said, “is that the dragon who owned the scale is dead. That’s the very best part.” She started walking toward the castle, lunging and thrusting as she went.

We followed.

“Be careful,” Bella called. She left my side and hurried to catch up to Meryl.

Rhys walked next to me. “I have a gift for you too, Princess Addie.”

I shook my head, embarrassed about wishing for one.

He reached into a pocket in his doublet and held out a smooth wooden ball not much bigger than a walnut shell. I noticed a thin seam running along the middle. “This is more than it seems.” He twisted the ball, and it opened along the seam.

The Two Princesses of Bamarre

The Two Princesses of Bamarre Dave at Night

Dave at Night Ella Enchanted

Ella Enchanted Ever

Ever Fairest

Fairest The Lost Kingdom of Bamarre

The Lost Kingdom of Bamarre The Fairy's Return and Other Princess Tales

The Fairy's Return and Other Princess Tales Stolen Magic

Stolen Magic A Tale of Two Castles

A Tale of Two Castles A Ceiling Made of Eggshells

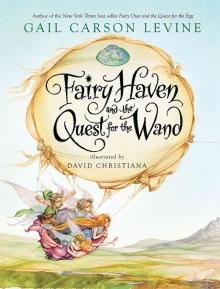

A Ceiling Made of Eggshells Fairies and the Quest for Never Land

Fairies and the Quest for Never Land The Wish

The Wish Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg

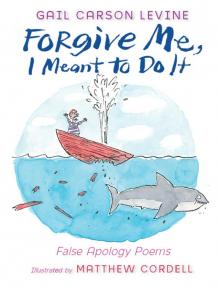

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It: False Apology Poems

Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It: False Apology Poems Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand

Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It

Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It