- Home

- Gail Carson Levine

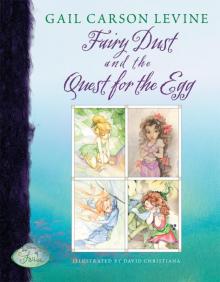

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg Read online

Text by Gail Carson Levine

Art by David Christiana

Copyright © 2005 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may

be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording,

or by any information storage

and retrieval system, without

written permission from

the publisher.

For information address

Disney Press, 114 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York 10011-5690.

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file.

ISBN 978-1-4231-4333-8

Visit disneyfairies.com

Table of Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

ONE

WHEN BABY Sara Quirtle laughed for the first time, the laugh burbled out of her and flitted through her window. It slid down the side of her house and pranced along her quiet lane. It took a right on Water Street, and frolicked on to the wide sea that separated the mainland from Never Land. There the laugh set out, skipping from the tip-top of one wave to the tip-top of the next.

But after two weeks of dancing over the ocean, the laugh veered too far to the south. It would have missed the island entirely if Never Land hadn’t moved south, too. The island was looking for the laugh.

The fact is, you can’t find Never Land if it doesn’t want you, and if it does want you, you can’t miss it.

The island is an odd place. The humans (or Clumsies, as the fairies call them) and the animals who live there never grow old. Never. That’s why the island is called Never Land.

The only reason the island rides the waves is because Clumsy children believe in it. If a time ever comes when they all lose faith, Never Land will lift up and fly away. Even now, if a single Clumsy child stops believing in fairies, a Never fairy dies—unless enough Clumsy children clap to show that they believe.

Sometimes the island is huge, and sometimes it’s small. Its inhabitants mostly live near the shore. The forests and the plains and Torth Mountain, where the dragon Kyto is imprisoned, are largely unexplored.

As soon as the island moved, Mother Dove knew a laugh was on its way. High time, she thought. She felt lucky whenever a new arrival was coming. And the fairies would be jubilant.

She told Beck, the finest animal-talent fairy in Never Land. Beck told her friend Moth, who could light the entire Home Tree with her glow. Moth told Tinker Bell and eight other fairies.

You see, when a baby laughs for the first time, the laugh turns into a fairy. Often it turns into a mainland fairy—a Great Wanded fairy or a Lesser Wanded fairy or a Spell-Casting fairy or a Giant Shimmering fairy. Occasionally it turns into a Never fairy.

Word spread to all the talents. Each one wanted the new fairy, and each one made an extra effort to deserve her. The keyhole-design-talent fairies whipped up a dozen fresh designs. The caterpillar-herders found a caterpillar that had been missing for a week. And the music-talent fairies, who had just lost a fairy to disbelief, practiced an extra hour every day.

Approaching the island, the laugh slipped under a mermaid’s rainbow. It breezed by the pirate ship in Pirate Cove, too silly to be scared. When it touched shore, it sped up and hurtled along the beach, not even pausing to admire the flock of giant yellow-shelled tortoises.

The laugh shrank and became more concentrated. After it passed the fifty-fourth conch shell, it canted inland. It hadn’t gone far, however, before the air hardened against it. The laugh was forced to slow down to a crawl.

The trouble was that Never Land was having doubts. This laugh was a little different, and the island wasn’t sure whether to let it in.

Below lay Fairy Haven. Fairies were flying in and out of their rooms in the Home Tree, a towering maple that is the heart of Fairy Haven. Fairies were washing windows, taking in laundry, watering windowsill flowerpots—making everything shipshape in honor of the evening’s celebration of the Molt.

The laugh sensed it belonged down there. It tried to descend, but it couldn’t.

In the lower stories of the Home Tree, fairies were busy in their workshops. Two sewing-talent fairies were rushing to finish an iris-petal gown. Bess, the island’s foremost artist, was putting the finishing touches on a portrait of Mother Dove.

If Bess—or any of the others—had known the laugh was overhead, she’d have flown out her window and helped it along. She’d have called more fairies to help too. And they’d have come, every single one—even nasty Vidia, even dignified Queen Clarion.

On the tree’s lowest story, fairies bustled about the kitchen, unaware of the laugh. Two cooking-talent fairies hefted a huge roast of mock turtle into the oven. Three sparrow men (male fairies) argued over the best way to slice the night’s potato. And a baking-talent fairy consulted with a coiffure-talent fairy over the braiding of the bread.

Above, the laugh pushed on, fighting for every inch.

It passed above the oak tree that was the Home Tree’s nearest neighbor. The laugh had no idea that a crew of scullery-talent fairies was working under the tree. Protected by nutshell helmets, they were collecting acorns for tonight’s soup.

In the barnyard beyond the oak tree, four dairy-talent fairies milked four dairy mice. The fairies failed to see the laugh’s faint shadow as it crossed over each mouse’s back.

In the orchard on the other side of Havendish Stream, a squad of fruit-talent fairies picked two dozen cherries for two dozen cherry pies. If only they’d looked up!

The laugh reached the edge of Fairy Haven where Mother Dove sat, as always, on her egg in the lower branches of a hawthorn tree. The nest was next to the fairy circle, where tonight’s celebration would be held.

Did the laugh feel the pull of Mother Dove’s goodness? I don’t know, but it bunched itself for a final effort.

If Mother Dove hadn’t been distracted, she’d have felt the laugh. But she was listening as a fairy recited her lines for a skit tonight, and she was watching as another fairy practiced her flying polka. Mother Dove wanted to nod encouragingly to them, but she had to keep her head still so Beck could brush her neck feathers.

Overhead, the laugh pushed with all its might. At the same moment, Never Land decided to let it in.

It spun once, then zoomed faster and faster, above Mother Dove, back over the orchard, past the mice and the oak tree, on a downward course. It achieved final sneeze force and exploded right outside the knothole door to the Home Tree.

And there, in the tree’s pebbled courtyard, was Prilla, the new fairy, flat on her back, one wing bent, legs in the air, the remnants of the laugh collecting around her to form her Arrival Garment.

TWO

MOTHER DOVE knew the instant Prilla arrived. “The new fairy’s come!” she told Beck excitedly. “Isn’t that wonderful?”

“It is,” Beck said, hoping the newcomer was an animal-talent fairy. In the courtyard, a crowd gathered around Prilla. A message-talent fairy flew off to tell the queen.

Terence, a fairy-dust-talent sparrow man, sprinkled a level teacup of fairy dust on Prilla. Not a particle more than a cup nor a particle less, mind you. It was Prilla’s first daily allotment.

As soon as the dust touched her, a tingly feeling spread over her, and her glow began. Fairies glow lemon-yellow, edged with gold.

She sat up. Her bent wing sprang back, and her wings started to flutter. Her mind cleared. She was a fairy! A Never fairy! She was so lucky!

The other fairies waited, feeling too solemn even to smile at the new arrival. Each fairy hoped against hope for a new talent member.

They expected her to announce her talent. The first act of every new fairy was to make The Announcement.

But Prilla flew over the courtyard, her brown hair streaming out behind her.

Flying was marvelous! She turned an aerial cartwheel.

And she had magical powers, didn’t she? She flew to the Home Tree and shook a little fairy dust off her hand and onto a leaf. She squinted hard at the leaf, and it flickered out of sight. She blinked, and there it was again.

The fairies on the ground stared up at her. Not one of them had ever seen an arrival behave as Prilla was behaving. She landed in their midst, between Terence and a caterpillar herder.

They drew back.

“Greetings!” she said. “I’m so glad to be a fairy! Thank you for having me.”

Several fairies raised their eyebrows. Did this newcomer think they’d picked her?

Prilla saw their expressions and faltered. “Er, I’ll try to be a good fairy.”

A fairy said, “My, she’s freckled.”

Terence said, “Pleasantly plump, though.”

These were the sorts of things one said at an arrival, ordinarily after the new fairy had announced her talent.

“I swear they look younger every year,” the caterpillar herder said. A few fairies nodded.

Prilla wouldn’t look young to you. She’d look grown-up, just about five inches tall, same as any other fairy, and perfectly proportioned. Fairies, however, knew that Prilla was a youngster, because her nose and the lower halves of her wings hadn’t yet reached their full growth.

A grown-up Clumsy wouldn’t see Prilla at all. He might see the air shimmer. He might smell cinnamon. He might hear leaves rustle, but he’d have no idea he was in the presence of a fairy.

Adult Clumsies can’t see or hear Never fairies, although they can feel them. If a fairy pinches a grown-up Clumsy, the Clumsy will slap the spot, thinking he’s been bitten by a mosquito.

Tinker Bell landed in the courtyard. When she’d seen Prilla flash by her workshop window, she had dropped her leaky ladle and come. She wanted to be on the spot if the new fairy turned out to have a talent for repairing pots and pans.

Terence smiled his most charming smile at Tink. He admired her enormously. He liked her bounce when she landed. He liked the arch of her eyebrows, the curl to her ponytail, and her bangs, which were the perfect length, whatever length they were. He even liked her scowl, which was both fierce and pert.

Tink ignored the smile. Her heart had been broken once, and she wasn’t going to endanger it again. “Welcome to Fairy Haven,” she told Prilla. “What’s your name, child?”

“Prilla.” Prilla held out her hand to shake.

Tink hesitated, then shook. Fairies didn’t usually shake hands. “I’m Tinker Bell.”

Prilla said, “Pleased to meet you, Miss Bell.”

The bystanders exchanged glances. Tink frowned.

Prilla blushed. She knew she’d said something wrong, but she had no idea what.

It was this: Never fairies called each other by their names. Just their names. No miss or mistering. And only Clumsies said Pleased to meet you. Never fairies said I look forward to flying with you, or, for short, Fly with you.

“Call me Tink. What’s your talent, Prilla?” Tink waited, barely breathing.

Prilla stopped seeing and hearing what was around her. Instead, she heard the strains of a waltz and Clumsy voices. She was back on the mainland, standing on the shoulder of a Clumsy girl who was riding a carousel horse.

The girl felt Prilla’s wings beat against her neck and reached up to brush away what she thought was an insect. Prilla flew around to face the child, who turned slack-jawed with astonishment.

What fun! Prilla executed a perfect split and a double somersault.

Tink felt ignored. “Prilla, what’s your talent?”

Prilla’s grin faded. “Pardon me. What did you say?”

Tink tugged on her bangs. “Nobody says Pardon me. I said...” She spoke louder. “… what is your talent?”

“Talent?”

“Uh-oh,” Terence said.

A wing washer said, “Is she a giggle shy of a full laugh?”

This happened sometimes. A piece of laugh would crack off on its way to the island, and the fairy would arrive incomplete. Some incompletes had no ear tips, or they’d glow on only half their bodies. Some looked complete, but they had a speech problem or they thought the word chicken rhymed with mattress.

In Prilla’s case, the opposite was true. When Sara Quirtle laughed her first laugh, some of Sara stuck to it and went into Prilla. Prilla was fully a fairy, but she was more, as well.

“Par—er, excuse me, what’s a talent?” Prilla asked.

The other fairies fluttered their wings, appalled.

“Nobody says Excuse me either,” Tink said. “A talent is a special ability. All of us have one. We know what our talent is, from the moment we arrive.”

Prilla couldn’t think of a single thing she was good at. She blinked back tears. “I don’t think I have a talent.”

THREE

A BREEZE WHIPPED by Prilla’s ears, and a fairy flew into the courtyard. She was Vidia, the fastest of the fast-flying-talent fairies. She landed before Prilla, and smiled. Prilla didn’t like that sugary smile. Tink said, “Go away, Vidia.” Vidia said to Prilla, “Fly with you, dear child.”

“P-pleased to meet you.”

“Mmm. Incomplete, are we?” She leaned in close. “Dear child, if fast-flying is your talent, I have something that—”

“Vidia!” Tink said. She’d have to tell the queen about this. “You’d better—”

“Tink, darling…”

Prilla thought the darling sounded like a sneer.

“...you have no idea—”

A sparrow man shot straight up into the air. “Hawk! Hawk from the west!”

Tink shoved Prilla through the knothole door to the Home Tree. The other fairies flew into the lower branches.

Prilla and Tink watched the shadow of a bird cross the courtyard.

“That was a hawk?” Prilla said.

Tink nodded.

“Would it have eaten us?”

“If it was hungry.”

Hawks kill several fairies every year. Tink had had some close calls with them. She told Prilla, “Always keep a sharp eye out for hawks.”

Prilla shuddered. “When it’s safe, I’d like to thank that sparrow man. He saved us all.”

Tink tugged her bangs, irritated. Something was wrong with Prilla, and when something was wrong, Tink wanted to fix it. That’s why she loved repairing pots and pans. But she didn’t know how to fix Prilla. It was like having an itch she couldn’t reach. “Don’t thank him. He’s a scout.”

Prilla looked blank.

Tink thought, I’m going to pull every hair out of my head. “Scouting is his talent. Saving us was his joy.”

“I see,” said Prilla. But she didn’t.

Tink believed Prilla really had a talent but just didn’t know what it was. She looked down at Prilla’s hands. They were on the large side, but not too large. The child could be a pots-and-pans fairy. The strangest one ever.

Prilla was on the mainland again.

She was on a breakfast table, next to a container of milk, eye-level with the words Dietary fiber 0g on the container.

A man stood at the stove, pouring coffee. A boy was eating a muffin. Prilla flew in front of the boy’s face, fascinated by his chewing.

“Look!” Crumbs and saliva shot out of his mouth. He lunged at Prilla. She retreated. He knocked over the milk.

She winked at him and was gone. Laughing, she told Tink, “I just saw a Clumsy spit out half a muffin.”

Tink pulled her bangs. “What Clumsy?”

“The one...” Prilla realized she’d said something wrong again. Didn’t Tink blink over to the mainland sometimes?

Of course Tink didn’t. Most fairies had no contact with Clumsy children (other than the lost boys), unless a fellow fairy was dying of disbelief.

Prilla changed the subject. “Are we inside the Home Tree?”

“This is the lobby,” Tink said, glad to talk about something reasonable.

The walls were golden brown, so highly buffed you could almost see your reflection.

Tink added proudly, “The walls are polished weekly, and it takes two dozen polishing-talent fairies to do it.”

Prilla wondered if polishing might be her talent.

Next to the knothole door was a brass directory that listed each fairy, along with her talent, her room, and her workshop, if she had a workshop.

“Your name will be up there, too,” Tink said, “in an hour or so, when the decor-talent fairies are through with your room.”

Prilla nodded. She’d be the only one without a talent next to her name.

The lobby floor was tiled in pearly mica. A spiral staircase rose to the second story, although the fairies used it only when their wings were wet and they couldn’t fly.

Four oval windows faced the courtyard.

“The windowpanes are reground pirate glass,” Tink said. She thought longingly of her leaky ladle.

A clatter and a bang and raised voices came from the corridor beyond the lobby.

Prilla turned to Tink for an explanation.

Tink’s heart raced. Something might have broken that she could fix. “Would you like to see the kitchen?”

The Two Princesses of Bamarre

The Two Princesses of Bamarre Dave at Night

Dave at Night Ella Enchanted

Ella Enchanted Ever

Ever Fairest

Fairest The Lost Kingdom of Bamarre

The Lost Kingdom of Bamarre The Fairy's Return and Other Princess Tales

The Fairy's Return and Other Princess Tales Stolen Magic

Stolen Magic A Tale of Two Castles

A Tale of Two Castles A Ceiling Made of Eggshells

A Ceiling Made of Eggshells Fairies and the Quest for Never Land

Fairies and the Quest for Never Land The Wish

The Wish Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It: False Apology Poems

Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It: False Apology Poems Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand

Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It

Forgive Me, I Meant to Do It